Dark Down Under: wondrous Australian modern folk band Bush Gothic

A 2016 fRoots article from the archives to celebrate the upcoming album

It’s an exciting time of year. Yes, May the 4th be with you (I am massive Star Wars fan, but don’t talk about it online much as I’m hideously behind with the TV series and am trying to avoid spoilers). But also, one of my absolute favourite bands, Bush Gothic, have a splendid new single out now and new album due very soon. The single is a version of the traditional song ‘Lady Franklin’s Lament’, whilst the album will have the improbable name of What Pop People Folk This Popular. I will write more about it once the whole album is out and I’ve had time to digest it a bit. The trio are hoping to make a UK tour happen around February next year, so do start spreading the word so we can prove there is demand and ensure Brits don’t miss a rare chance to see them in the flesh.

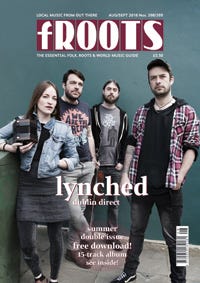

Until then, I thought I’d share a piece I had published back in 2016 in the late, lamented fRoots magazine. This is shared here with the permission of the magazine’s founder and editor, Ian Anderson. This is the version I submitted, so might deviate slightly from the published text in the mag.

START

Ahead of their UK tour, Christopher Conder talks to Jenny M. Thomas of Bush Gothic about the darkness at the heart of Australian folk songs

I was in Australia last year. I think you are allowed to count a country as ‘visited’ once you have left the airport, and I make the above claim on that proviso; my time there consisted of a half-hour walk outside Brisbane airport. As I picked my way over the boggy land alongside the main road, I gratefully gulped down lungfuls of luscious warm air. But the sustained attack of hundreds of ferocious biting insects soon forced me back inside again.

I was near the end of a 39-hour journey to the Solomon Islands. To keep me entertained through four different flights, I’d aimed to load my MP3 player with music from each of the countries I was stopping over in. My album to represent Australia was Bush Gothic by Jenny M. Thomas and the System. It’s a masterful collection of Aussie folksongs, sung by the eponymous Jenny and dynamically accompanied on violin, piano, double bass and drums.

I first saw Jenny perform around a decade ago at the Bedford Hotel in Sidmouth. Her stark solo fiddlesinging stayed with me, and in 2012 I got in touch to ask when she would next be in England. We started an online correspondence that’s continued over the ensuing years. With eight hours to kill in Tokyo airport on the way home from my Pacific adventure, I sat down to listen to the bluesy Japanese sounds of Shunsuke Kimura and Etsuro Ono and tapped out an e-mail to Jenny. A few days later, Jenny replied. The joys of two children, regular orchestra commitments and the cost of flights had kept Jenny in the Southern Hemisphere for the last decade, but it was with much excitement that she told me of her return to the UK as the support act for her countrymen, the Spooky Men’s Chorale.

Several months later and Jenny was sitting at our dinner table, along with her Bush Gothic bandmate and sometime Spooky Man, Dan Witton. Joining us were fellow fRoots writer Ken Hunt, his wife Santosh and the renowned Indian violinist Kala Ramnath. My partner, two more friends and a lovable old Jack Russell also managed to squeeze into our front room and a merry time was had by everyone. Then we suggested Jenny and Kala play for us.

They both sat on the floor, legs crossed, their backs against the window, violins poised, and improvised together. Tuppence the dog voted with her feet and padded out of the room, but the rest of us watched in gobsmacked admiration.

“It was a little intimidating,” Jenny confides, recalling that evening as we conduct this interview over Skype. “I tend to focus on one particular technique at one time, and for the last couple of years it’s been classical viola and composition. The Indian classical technique is so thorough that in order to feel comfortable, you have to be playing it every day and I wasn’t. So I chose not to do the traditional Indian forms that Kala was offering; I decided to mix it up a little bit and go for a more open and melodic strand. Which I hope was pleasing for all!”

It’s morning for me in London, but the flame-haired Jenny I see on my screen is reaching the end of an energetic day of tree climbing in the Dandenong mountains with her children. Jenny is fourth generation Australian on both sides of her family, her ancestors being of Irish and Welsh1 extraction. “Poor desperate settlers, but no convicts' blood I’m afraid,” she laughs from her Melbourne kitchen, her broad Aussie accent full of good cheer.

She can pinpoint the exact moment she decided to sing Australian settler songs. It was on the 13th of March 2004. Until this point she’d done everything but. She grew up playing in church, got a qualification in classical viola, spent time in Ireland learning local fiddle styles, was taught by Arto Järvelä in Finland, studied Carnatic Indian violin, toured with ‘chamber pop’ group Naked Raven, joined a load of good time Celtic bands and had wild times composing electro-acoustic soundtracks in the Circus Oz Band. Then followed several years leading the Australian world music fusion group Akin, and the release of a now hard-to-find solo album of instrumental pieces called Into the Ether.

“Akin did a lot of touring, so I went to a lot of folk festivals”, she remembers. “Every single time I saw what we call ‘bush bands’, playing Australian folk music, I’d have to walk away. It was really jolly, up-duh-duh-duh-da! It was just straight ahead three chords and it seemed to be very masculine, I suppose. It didn’t appeal to me.”

That March in 2004 she had the radio on while caring for her five-month-old baby. “I was listening to my very favourite programme, which is called The Music Show [on ABC radio]. I was listening to this young man singing an English song, ‘Early one morning, just as the sun was rising…’ I listened to it and all of a sudden it exploded into these beats and beautiful string lines. I went, ‘What’s this?!’ It was Jim Moray. They interviewed him and I thought, ‘Fancy that, an English person singing English songs.’ It was so right. I thought, ‘why aren’t I playing Australian songs?’ Every single festival I went to, we were always doing Irish songs, American songs, Scottish songs. Imagine the most daggiest thing you could possibly wear that you threw out ten years ago. That’s half as daggy as it was to sing Australian songs! But I thought, it really should be done. I didn’t tell anyone for a long time,” she reveals. “I was too scared!”

Eventually she asked two Melbourne jazz musicians, Christopher Hale and Anthony Schultz, to accompany her on what became her 2006 album, Farewell To Old England Forever. It features reworkings of old chestnuts like Waltzing Matilda and Bound For South Australia as you’ve never quite heard them before, and an entrancing version of the lullaby, Little Fish. The trio toured for a while but by 2009 Jenny wanted to try something new and experimental, and the ‘bush band sessions’ began.

“It was very low-key. I booked a venue for every Saturday and had different musicians coming. It was a trial for them as much as for me. I have worked in enough bands and left enough bands to know that it’s as much the personality [of the musicians] as it is their musical intelligence that makes it work.”

For one gig drummer Chris Lewis and double bass player Dan Witton joined her. “Our audience was one currant bun sitting on a table all by itself,” she admits. “We ate it at the end!” It wasn’t the ideal audience, but she knew she had her band. “I’d worked and toured with Chris before in Circus Oz. He was my musical director and I was always really inspired by his playing. I would have been too sad to have used any other drummer. I did work with a few different bass players,” she confesses, “but Dan played for about two minutes and I knew quite strongly he was an exceptional musician. His choices of melody and with harmony were very free. Then he sang a little bit of backing harmonies and I almost fell over, because his voice is angelic. I just had to have him. And I did.”

At first they were Jenny M. Thomas and the System, and their album was called Bush Gothic, but they liked the latter name more and took it for the band. The term was coined to describe the work of an early twentieth-century writer called Barbara Baynton. “She wrote these stories which were very dark and actually very truthful about what happens in the Australian bush, exploring what would happen to settlers’ wives who were left alone when the men would go off shearing. They could often be by themselves, surrounded by 50 kilometres of bush before the next neighbour, and it was kind of terrifying. She would write about this when most other writers were writing about the lucky country and how you can make money off the sheep’s back. Of course, both are the reality of Australia. It’s a wonderful land of opportunity and it’s a paradise. But there’s also this underlying feeling of great homesickness and fear of this strange land, where everything looks and smells different, the temperature is different and the natives don’t want you there.”

It is this dark heart that Bush Gothic capture in the Australian folk songs they perform. Take Botany Bay, which Jenny has recorded in different arrangements on each of her last three albums. “I’ve sung it ever since I was a kid. At its heart is its chorus, ‘toora-li, oora-li’, which suggests ‘oh well, she’ll be right’,” she grins. “But it’s quite a melancholy story. It’s so Australian. That’s why I keep doing it.”

The latest recording is on Bush Gothic’s newest release, The Natural Selection Australian Songbook. On it they’ve teamed up with four hand-picked musicians – Rachel Johnston, Jason Bunn, Edward Antinov and Sarah Curro – and dubbed them the Lonely String Quartet. “Well, the string quartet has been described as the most perfect ensemble on Earth, and I think I have to agree with that,” Jenny explains. “As a composer I wanted the challenge of how to really write for string quartet and utilise everything that the instruments can do, but also how their voices can interlock.”

The album is just as rewarding as the first Bush Gothic release. The Indian influences are more prominent and overall in has a slightly lighter touch. As well as the traditional numbers, the trio tackle contemporary Australian songs for the first time. The Songbook opens with a cover of John Williamson’s Aussie country classic, True Blue. It’s often considered a rather bombastic celebration-cum-requiem for true Australians – that is, we infer, working-class, white ones of British extraction. “A lot of people really hate it,” Jenny tells me. “I hated it! What the song represents is a very narrow view on who Australians are.” But by taking it out of context, Bush Gothic reveal a different side to the song. The questions in the chorus, which seem rhetorical in other recordings, sound like a genuine attempt to understand what it is to be Australian when sung by Jenny. “Is it me or you? Is it Mum or Dad? Is it a cockatoo?”

“Australians are complex people,” she considers. “We’re fed this line that we’re these happy-go-lucky people who love being outdoors. That doesn’t even scratch the surface. Until the last ten years, I rarely saw myself represented in artistic practice. Now, I think we’re more confident. A big part of it is coming to appreciate the indigenous culture here. They have so many secrets and so many insights which are absolutely extraordinary. Non-indigenous Australians are starting to realise the treasure that that is. And slowly, slowly, we’re starting to feel more at home here.”

END

Chris

P.S. I’ve stumbled across this hidden on the Bush Gothic website - lyrics to and a short explanation of some of their songs from a Melbourne concert recital (somehow there being a programme makes it a recital rather than just a gig!). It includes the song ‘Great Southern Land’ by Icehouse, a cover that is appearing in recorded form for the first time on the new album.

Jenny went on to explore her Welsh heritage in more detail via Bush Gothic’s collaborations with Angharad Jenkins, and her own concerted efforts to learn the language, culminating in her Welsh language choir, the Côr of The Matter.